When I interviewed my friend Ross McMeekin for my course The Writer’s Welcome Kit, he mentioned that reading the slush pile, taking the first climb through the mountain of submissions for a publication, served as one of the best pieces of education he ever received.

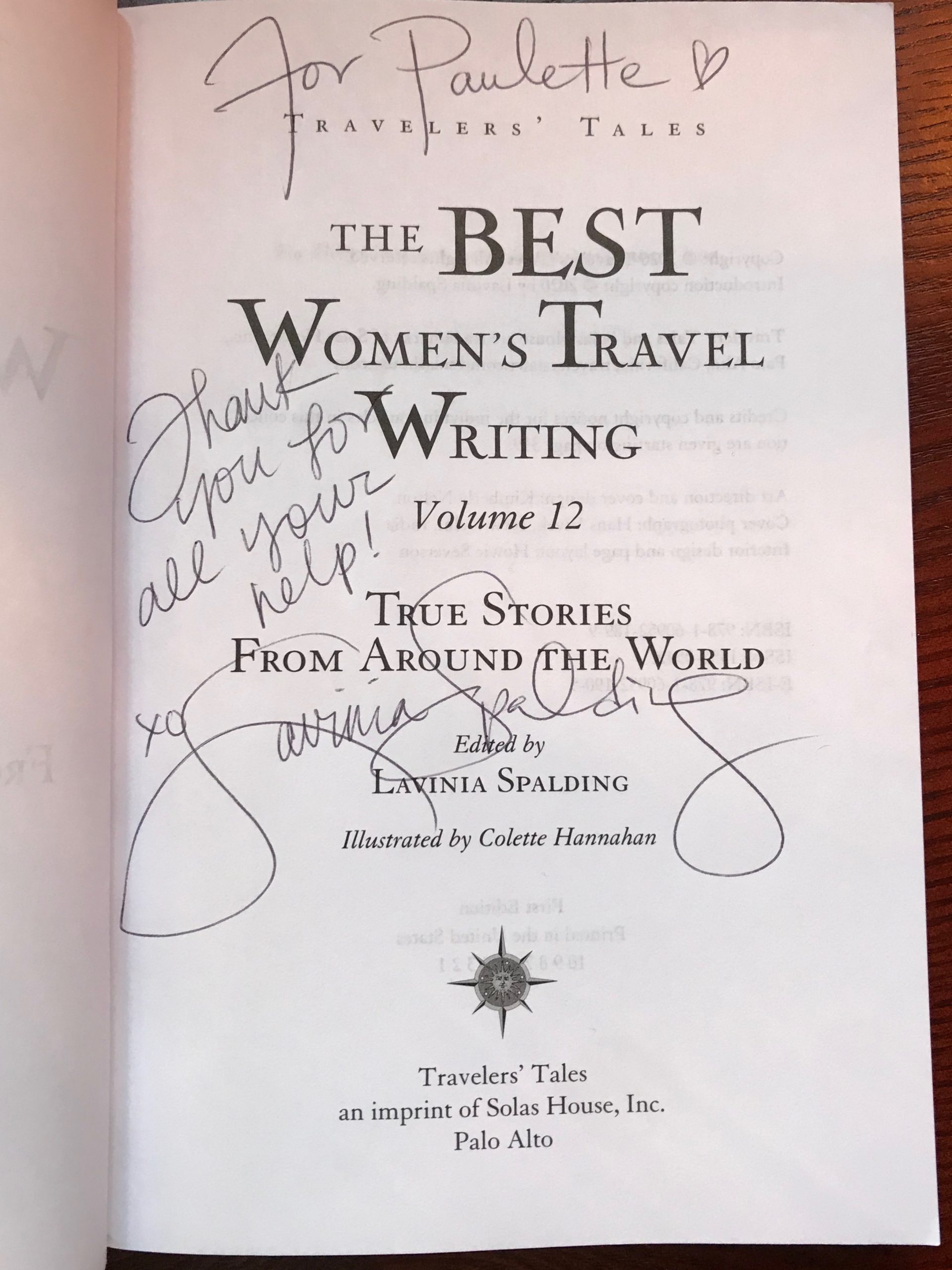

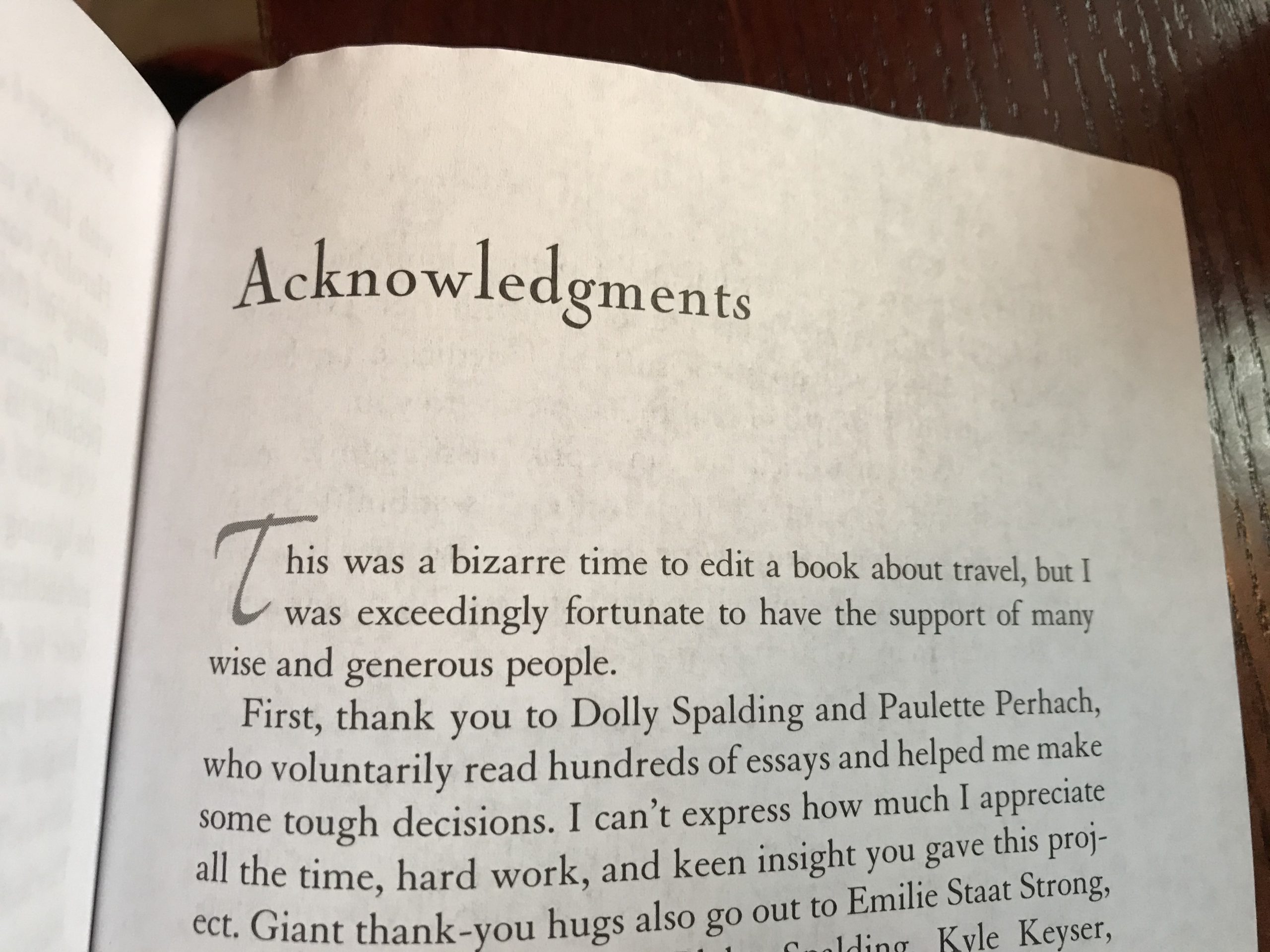

Years later, while chatting with Lavinia Spalding, the editor of the Best Women’s Travel Writing Anthology, I mentioned that I still hadn’t had the experience. “You can read for me!” she said. She had a pile of 1,200 essays awaiting to be whittled down to the 34 that would make up her anthology.

I volunteered.

Defining the dream

Deep down in me is the dream: I want to be a travel writer (along with all the other kinds of writer I want to be. Novelists, essayist, etc. It’s a real problem). What does that even mean, to “be a travel writer,” in an industry that’s in such flux?

I want to have adventures. I want to write about them. I don’t quite know how to go after it.

Sometimes I wonder if, growing up broke, I thought getting someone to send me places was the only way I’d be able to afford to go. Maybe I should just make money, send myself, and write essays afterward?

The voice in my head says, “You’ve traveled. You’ve spread at least a down payment on a house around the world. (Note the conspicuous lack of an owned house). Colombia, Nigeria, Myanmar. You can write essays. So just do it already.”

I’m almost 40, and I haven’t “become a travel writer,” which to my mind means the person the editor at That Travel Section calls up to be like, “Paulette! We need someone to kayak the Amazon river and report back. Are you available???”

But I’m not dead, I’ve gotten three travelish pieces published so far, and I can always re-dream, to be a traveling essayist, to try to create the kind of work that might end up in the kind of anthology Lavinia curates.

I dove in.

Wow, yeah, I suck at this

To read the kind of work you want to do over and over is to see your same mistakes mirrored over and over back at you. As I went through the digital pile, I saw plot lines repeated time and time again, plot lines I have in my computer as we speak in the form of my own drafts:

- It was a big risk but I did it!

- I was scared but I did it!

- I hooked up with someone in an exotic location and now I’m more interesting!

After reading just a few dozen, I understood why so many of my submissions had been answered with tumbleweeds rolling through my inbox.

The best stories were specific, unique, and surprising. They zoomed way in or way out. The best of them showed me what I still had to learn.

My new advice for myself about travel writing

Here’s what I learned for myself, the things I’ll be saying in my head as I pursue publishing more writing about where I’ve been and what I’ve done.

Don’t write about Italy or France unless you have something killer

Everyone’s writing about Italy and France. We know. The croissants were flakey. The hills rolled into the horizon. The wine? Chef’s kiss.

What’s up in Tunisia though?

Beware the curse of knowledge

When you travel somewhere, it becomes a part of your soul, and it can be really hard to extract that as you build it for a reader, rendering it for eyes blind to your experience.

I saw this curse of knowledge taking shape in several ways, which could be rectified thusly:

Tell us how much the money is.

If you say you paid 10,000 ₩ for something, to those who have never been to South Korea, it means nothing. Either calculate the literal amount in dollars or in relation to how you feel about it. Was it cheap or pricey, like the €12 bottle of water I got in Geneva, so shockingly expensive that the person with me rolled up the receipt and pretended to snort the rest out of his glass?

Relate it to life that we, most likely dumb Americans, know. Was your coffee half the price you’d pay at Starbucks? Was your cab ride, like the one I took in Japan, having casually misplaced the decimal in my mental exchange, the price of a car payment? ($200 ok?! It was $200!)

Tell us what the word means

In my life, I have only thrown two books across the room. One was by Al Gore. The other delivered a chapter-ending punchline in French.

I know, those words go from guidebook pages to rolling off your tongue and it’s so fascinante.

But if you just italicize the word, that does nothing for us if we don’t know that it means, for example, fascinating. It alienates and frustrates us. We’re no longer on the trip with you. Is it worth getting up and looking up that word? Maybe, or you could just do us a solid and introduce us to your new friend.

Unless it sounds very similar to the English equivalent, either repeat it in English, or tell us what it does. Something like: “Mba’e,” he said, giving me the informal greeting.

Some writers did this very smoothly, weaving in a wink to the meaning. It doesn’t have to be a dictionary entry. Just take us along the journey.

Anne P. Beatty goes one step further to tells us how important the phrase is to the place. “Ke garne is one of the first Nepali expressions foreigners learn. Literally translated as “what to do?” the meaning feels closer to “what can you do?”

When you teach us a foreign word, feel free to use it again without explanation. That’s kind of fun for us. After reading Faith Adiele‘s book, I know now how to say foreigner in Thai: farang. She uses it dozens of times, and each time I know exactly what it means.

Tell us where the heck you are.

Once you’ve fallen in love with a place, it feels like everyone should know where the Urubamba Province is. We don’t. We, perhaps, went to public school in Florida.

What country are you in? If their currency is only used in that country, and we’ve heard of it, like yen, that’s a good clue.

Again, the artful hints felt the most rewarding. “In the country where Hitler once ruled.” Yep! Germany, we get it.

You need more than just details

Yes, definitely, give us those sights, sounds, smells. But they are not enough. They are not story.

You also have to give us a character who wants something, something that gets in her way, and a change she goes through during the trip.

Yes, you’re writing travel. But you’re also writing story. That means problems, stakes, choices, and consequences.

I read paragraphs, pages, of flowers and bridges and mountains and beaches that stood perfectly still, in a vacuum without dramatic tension. A lovely photograph, but not a story.

Relate it back to you

Every place has been written about. What I learned from the best of the writers is that what you’re really writing about is why it matters that you are in this place. The confluence of you and a place and a time.

Take, for example, this part of the intro from Alia Volz’s piece: “The highway winds through coastal Artemisa, a tranquil, verdant province of farmland and gleaming seascapes. Exquisite scenery. But I have an ulterior motive for returning. I’ve come to settle an old debt.”

She sees the place differently than anyone else. So do you.

Ask yourself:

- How is your personality at odds with your surrounding?

- What about the situation challenges the quirks of your particular ego?

- What do you see that others might miss?

“Why, little ol’ me?” you might ask. Yes, a story can still be about you without being an ego trip. It can be a gift to the reader. But there is no getting around the fact that this place is being experienced through your peepholes, and no one else’s.

Onward!

I’ll try to ignore what I perceive as a failure. Try to forget how many people are hustling to make it in this field. Focus on what I have to offer, now and in the future.

I have everything thing I need to move in the direction of travel writing. I just need to keep working at it. After reading about 200 examples, I feel much more prepared.

Need some inspiration? Get a free year of daily writing prompts by clicking below!