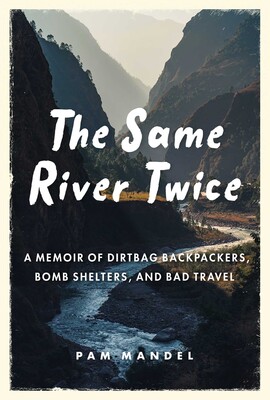

“That was fast!” Pam said after I finished her book, started it less than 24 hours earlier. Poor Pam. She’d spent so long getting this book out, but it was so good I just had to gobble it up.

Pam’s book, The Same River Twice, is a sprawling ride through the kind of analog travel most of us have ever known. Taking place 40 years ago, it follows Pam as a young woman trying to find a place in the world that feels like home, when home isn’t quite doing it. I had known Pam was a bad ass when I interviewed her for my podcast. Now I get the backstory.

Psst: This site uses affiliate links.

Psst: This site uses affiliate links.

I’m so happy this book found its way into the world. Much in the same way I post all my rejections on my Instagram, Pam kept us up-to-date on Twitter with her book proposal rejections. The total? 75.

She hung the hell in there. When you read this book, you’ll understand where she got her tenacity.

I felt like I did some cool travel, but no, Pam’s the Queen badass of dirtbag backpackers. I’ll take a hotel room, thanks!

Below is our conversation during her reading “at” Elliott Bay Books, with a transcript below.

If you’re looking to write up some of your old stories, I have a mini-course called 30 Days to the Personal Essay that can help!

My conversation with Pam Mandel, author of The Same River Twice.

Pam:

I had really wanted to do this in person because I’m a Seattle writer and Elliott Bay is sort of our cornerstone bookstore. There’s a lot of wonderful independent bookstores in Seattle, but Elliott Bay is the one that I know the best. And I used to have an artist studio in Pioneer Square. And I spent a lot of time in the old basement of the former Elliott Bay going for lunch, eating soup and bread and drinking coffee and talking nonsense with my friends and the new space is beautiful. It’s fantastic. And I was up there the other day and I have to say, I was really feeling kind of sad to see a bookstore that was not bursting with people. So I just wanted to, before we dive into all of this stuff if you have an Amazon order, I want you to cancel it and call either your local independent bookstore or call Bay and ask them to send you a copy because Amazon will be fine when all this is over, we’re getting all of our other stuff from them anyway. So if you can please support your independent bookstores. Cheers.

Paulette:

Yeah. So very much so. Well, thank you for inviting me to talk tonight. Super excited.

Pam:

I’m just going to read a really short chapter from the middle of the book. And then Paulette has a bunch of questions and hopefully we are going to take questions from you all. And again, I’m delighted that you’re here. It’s so nice. And it breaks my heart a little bit, that I can’t see your faces, but seeing you all say hi in the chat is really nice. So thank you for that. Alright. This really is right from the middle of the book. And just for context, I had been hitchhiking across Europe with my very bad boyfriend, and we ran out of money, and we got stuck on Corfu, and my very bad boyfriend called his dad and asked him to send money so we could get unstuck.

I don’t know what Allister told his father we were going to do with the money. I imagine they argued. I could picture his father telling him to come home. You’re not getting any younger son. I’m not going to make this offer forever. Allister saying it wasn’t going to happen. Maybe Allister lied, telling his father what he wanted to hear. Allister was mean and a petty thief. He could have been a liar too. His father wired a few hundred pounds, enough to give us time to decide what to do next, enough to get us both back to England if we went on the cheap, like we’d gone on the way down. We headed in the exact opposite direction, Southeast towards Athens.

I was as excited about Athens as I’d been about Paris. In school, I’d learned about Greece as the birthplace of Western democracy. I knew the names of the Greek philosophers, Socrates and Plato and Aristotle. I imagined the forum as a crowded Plaza where you can get coffee and discuss the meaning of existence with strangers. I wanted to see the columns of the Acropolis against the Greek sky to see where the marbles I’d seen in the British museum had come from. I was eager to visit another great European city, one important in art and history. A city people would look at you with interest when you said you’d been there. It mattered to me what people would think when I said I’d been to Athens. More specifically, what they’d say when I told them I hitchhiked to Athens. I wanted people to feel impressed with my travels.

The truth was not so impressive. I had been a tourist of the worst kind, taking advantage of the people of Corfu while remaining completely ignorant of the culture of the place. We were camping illegally. My boyfriend was shoplifting and working without a permit. I let the Island’s poorest residents feed me. It didn’t occur to me I was taking things away from them too. And it’s not like we got out of it ourselves. Allister’s father freed us from our open-air dead-end. I didn’t think about any of this. I just wanted to feel tough, worldly, like I could manage on my own anywhere, but I was just another cheap backpacker, barely contributing to the local economy. The tourists Allister liked to make fun of were better guests than we were.

When the wire transfer from Allister’s father came through we took the ferry back to the mainland. I wrote Athena on a piece of scrap cardboard in big block letters. We walked to the highway. We’d sit on our packs on the shoulder of the motorway, when the traffic was in a lull, jumping up when a car or truck appeared on the horizon. Getting rides was easy. The truck drivers always stopped. It was always middle-aged men. And they were always unfailingly kind. Even when I hitchhiked alone up and down the Island looking for work and back in Israel, it was always middle-aged men, sometimes Arab farmers, and they were always kind. I learned this from hitchhiking with Eli. If you acted like strangers weren’t dangerous, like they were friends offering help, they mostly responded in kind. I remember Eli every time I stood on the asphalt shoulder, watching the truck slow down and then stop. He always greeted the drivers with surprise and graciousness, like they’d given him a gift. I tried to do the same. I’d been hitchhiking for months, sometimes alone. And the only trouble I’d had was during my trip with Ronnie to Sinai, when that soldier grabbed me.

[aside]: Just a little bit of context, this is a callback to earlier in the book. And I’m talking about a guy that I hitchhiked all over Israel with and a girlfriend that I also did some travel with.

Allister and I were covering good distance on our way South until late afternoon when our ride dropped us at Walnut village, along the highway. We stayed on the shoulder for what felt like hours. A car would blow by every 15 or 20 minutes. Then they got further apart until traffic stopped altogether. The town, the field surrounding it, the highway, everything was silent. Even the birds had taken the afternoon off. The day was fading. There’s no hitchhiking after dark. People who can’t see you will not pick you up. We walked around looking for a restaurant, a guest house, anything open, any place to ask about camping for the night or to buy food, but everything was shuttered tight. Was it a holiday? Was it a Sunday? It could have been. We never knew what time it was, much less what day. I sat on the sidewalk with the packs. Allister’d circled the town, and then we’d switch places and I did the same.

The houses were hidden behind high stucco walls. The only sound came from the wind in the cornfields surrounding the village. The rows were tight against each other, the stock strong like young trees. Muddy dirt in what little space there was between them. We could not camp in the fields and it was corn fields as far as we could see. With each passing hour it looked more like we would pass the night on the sidewalk, waiting for dawn and the day’s next possibility of rides. The heat and silence grew heavy. We’d gone silent. No words were going to get us off the sidewalk. An hour went by too. The shadows got longer. A man appeared and beckoned for us to follow him. He was thin with dark hair, overdressed for the heat and long pants and a dark long-sleeve shirt. He opened a gate in the wall and led us across the back courtyard. He showed us to a neat little room with a big lumpy bed and calendar pages taped to the wall. After showing us the bedroom he led us under the backstairs of the main house to a little bathroom. The toilet flushed by filling a bucket and pouring the water into the bowl. We tried to give him some money, but he pulled his hands back, shook his head no. He disappeared and came back a few minutes later with a picnic and a paper bag. Hard-Boiled eggs, bread, strong cheese, oranges. We tried again to give him some money. And again, he refused. He put his hands together in a prayer sign and said something we could not understand. And was gone. I felt like I had dreamed him. It’s not obvious where he’d come from. And when he left out the gate of the courtyard, it wasn’t clear where he was going. Early the next morning we closed the gate behind us to walk the short distance back to the highway. And in no time we were climbing into the cab of a semi-truck.

I’m going to leave it there.

Paulette:

I love that scene. That was one of my favorites. I love those moments in travel where you’re like, are we going to our deaths or are we going to something we’ll never forget? To travel is to kind of throw yourself out there in a way. I had sensed about you, from knowing you, that you were just my kind of woman. And this book confirmed why. Everything that you’d been through and everything that you overcame and experienced and opened yourself up to, I just loved that. So why did you feel this story had to get out there, that after 40 years you’re like, this story needs to be told.

Pam:

Oh boy. So I’ve told this story a few times, and I’m going to tell it again. My friend Alex started this magazine called Fields and Stations, and it is a beautiful magazine. And when he launched this publication, he contacted me and asked me to write a memoir piece for the back of the book. I had been suffering from a really severe depression, and I said, “Alex, I’m not myself. And I can’t write, and I’m not going to do this for you right now. I love that you asked me, but I have nothing for you. I can’t do this right now.” He said, “Okay, I’m really sorry you’re having a hard time. And just so you know, I’m going to ask you again.” So Alex asked me three times, maybe four, and the last time that he asked me, he said to me, “Do I remember that you told me once that you had been in Sharm El Sheikh…”, which is this place at the bottom of the Sinai peninsula, “…before it went back to Egypt, while it was still Israel? Do I remember that you were there right during the transition?” And I said, “Yes, I was.” And he said, “Can you write about that for me?” And I said, “No, I cannot because of [reasons].” And he said, “Okay, but I really want you to think about this.” And I was like, “Yeah, Alex, I mean, you need to stop asking me this. It’s not going to happen. And thank you. And I just don’t remember that much about it.” So we were done talking and I put the phone down and I went and I turned on my computer and I wrote 1600 words and I sent them to Alex and he was like, “What happened?” And I said, “Well, you asked the right question, I guess.” And then it was like this tap was turned the floodgates were open and it all came behind it. And I was like, oh wait.

And I remembered all of it. I just remembered all of it. Now, the other thing that happened about the same time was a friend of mine, Jess Lowery, has this course called Rewrite for Life. And she gave me access to it. So I took her writing class. ‘Cause I was trying to make myself do things, right. I wasn’t writing, nothing was happening, and I did all these exercises. And through the course of these exercises I sort of tapped into this vein. It was the same vein that Alex sort of opened at the same time. It was like, oh, you’re really supposed to be writing some kind of Young Adult sort of thing. And I was like, that’s ridiculous. That’s not what I’m supposed to do at all. But again, they both sort of came together because, while it is not traditional Young Adult Fiction, my character, who is me, is very much a young adult at this very specific age of 17, 18, 19 through most of the book. And it absolutely fits that genre. So these two things kind of converged and then I couldn’t stop.

Paulette:

Mm love that. That’s incredible. So tell us about the scope of this trip. What is the scope in time and locations of the entire trip?

Pam:

So it starts when I’m 16 because I was a foreign exchange student in Sweden, but that’s really just a bookmark. It’s a reference. That’s my first real international travel. The rest of the book takes place when I go from the U.S. to Israel. Let me think, let me think. I should have drawn a map. I have to like piece this thing together. From the U.S. to Israel where I spend a great deal of time doing crazy things. I go back to the U.S. for a while, and then I go to London. We hitchhiked across Europe, which is where that scene is from. We run out of money in Corfu. We go back to Israel and then we go to Egypt, Pakistan, India, before I go back to the U.S. So the furthest place I get is up in the Himalayas in India. So it’s half the planet, maybe two-thirds, from suburban California to the Himalayas. And most of it is in the early eighties.

Paulette:

What’s interesting about it is that it’s a different kind of travel. I remember in 2017, I was traveling South America and I couldn’t Google anything, but I could call. So I would get in a bad situation and call my sister and be like, I need you to look up buses from Buenos Aires right now. And I never called her calm. I was always just freaking out, but it was so funny. ‘Cause I couldn’t . . . I had some capabilities, but not others. And you had no smartphone, no internet. So what were some things that happened on this trip that could not have happened if you had a smartphone, good and bad?

Pam:

Wow. I mean this whole business of getting washed up with no place to stay is of course something that just wouldn’t happen, right? You book an Airbnb, right? You book a hostel or something. You wouldn’t end up with nowhere to go. You would have a sense of your destination, but also I was truly uninformed about so many of the places that I had gone because I just didn’t have access to information about it. Everything was so shoestring and accidental. Most of this adventure was sort of accident. I wasn’t really prepared for it. And now I’m like, what are you insane? That’s no way to travel. I don’t know that I could even have gotten that far and stayed that uninformed now. It feels like it would be impossible to maintain that kind of naivete, right?

Paulette:

Yeah. I was reading when Jason Wilson, the series editor of Best American Travel, described your book as a love letter to a certain kind of beautiful aimlessness. And I loved that. And I feel like we’re kind of in this timeline now where it’s like a race to nowhere. What effect did that have on you to have this time of kind of beautiful aimlessness where you’re like, we’re here. How did that affect your worldview?

Pam:

So I’m an acute observer of things and I suspect that some of it goes back to that, right? When you can’t go anywhere and all you can do is sit, and you can’t disappear into your phone. All you can do is look at what’s around you. Then you can sort of collect your thoughts, write them in your journal and observe where you are. That’s such a good question. I like that so much. And I think that probably fed into why I am that acute observer, because I was forced to do that. I didn’t have a choice. You can’t sit on the side of a road waiting for a ride and not be present where you are. There’s nowhere to go. Again, you don’t have your phone to disappear into. Maybe I’d have a book with me. Maybe I didn’t. It sort of depended on where we were. Sometimes I would read, but you know there’s only so much of that you can do when you’re hitchhiking, because you need to be present. So that ability to be present and look at the world around you . . . it’s probably where some of that comes from.

Paulette:

Is there anything that you do now where you say, oh, this reminds me of my adventure.

Pam:

There are small things that will make things spark. But travel’s really different now. Although there is a thing I do now, where once I get to the airport I have this sense that all the things that are going to happen are outside of my control. I’m like everything that happens from this point forward until maybe I am in a hotel room or something at my destination is totally up for grabs, right? Like I’m not flying the plane. I don’t control the weather. I don’t get to decide who I’m sitting next to. And that, that feels like the only place where I can really feel that way. Mostly I’m traveling with an agenda or a destination, or I have something I’m supposed to be doing. You can still get this kind of vibe from a road trip, and I still love to go on big road trips that are really unstructured. I knocked around the Mississippi Delta for 10 days, a couple of years ago, and it really felt like that kind of thing, because I didn’t have an agenda. I would stop and be like, I guess I’m going to have lunch there. And then things would happen. I would have conversations. They would be very unexpected and not the kind of thing that would happen at home. And I would just be like, this is out of my control, you know? So you still have that kind of a serendipitous interaction, but you have to make space for it. You can’t be scheduled to the eyeballs for that stuff to happen.

Paulette:

Totally. And what about traveling with no money? I had a time where I had to couch surf in Colombia and I got locked in an apartment with an old lady and a chicken, with my friend Tessa. She could not understand our Spanish and we could not understand her. And we had to just sit there and wait for someone to let us out. And I was like, this would not have happened if we had money for a hotel, but we were trying to stretch our time as much as possible. I think that there’s something to be said for the creativity that brings. What were some of the benefits of having to do it on such a shoestring?

Pam:

You know, I don’t think anybody should intentionally travel with so little cash. It’s foolish and also it can be exploitative. So there’s that aspect of it where if you have that little, then what are you doing? What are you doing? I don’t know why you’re out there when you have alternatives. And I realize this is coming from a place of terrific, tremendous privilege for me to say this, but most of the people that are doing that kind of travel have options, even if they don’t believe they have options. So I mean this story where we call home, Alister calls his dad and he sends us the money to bail us out. We had options. So being that kind of cheap can be really harmful, I think in all kinds of ways. But that said… I don’t hitchhike anymore and I kinda miss that. HItchhiking was great. I pick up hitchhikers sometimes. When I’m in Hawaii, I pick up hitchhikers all the time. I love picking up hitchhikers ‘cause I remember what that’s like. It gives you these opportunities to meet people that you wouldn’t otherwise encounter. When you have money, you’re going to take the bus, you’re going to take the train, you’re going to fly. You’re going to do these other things. You’re maybe not necessarily going to do hitchhiking as your first thing, but I really like that. And again, it was very rare, very rare that I experienced any kind of a danger. People just wanted to talk.

Paulette:

Someone posted in the comments, all caps, “STRANGER DANGER.”

Pam:

No! Stranger danger is not a real thing! It’s just to make us feel afraid of people.

Paulette:

There’s a lot in your trip that you’ve said makes you cringe a little bit. What is something that you will always feel like, you know what, I did that, and I’m really proud of myself….that was a formative thing for me to know that I did that…. And no one can take that away from me?

Pam:

There’s part of a trip where I am traveling in India by myself. And I don’t really know where I’m going and I’m supposed to get back to this place to reconnect. So, more context: we’re going to go on this trek and I get a bad cold. We were going to go across this mountain pass and I’m sick. So I was like, I can’t do it. I’m not going to slog through six feet of snow. I’m not going to go up in the mountains with this cold. I’m going to go back to town, which was, I don’t know, two, three days’ bus trip away. But the first thing I had to do was walk back out of the mountains, which I did on my own. And I remember meeting these Australian girls who were doing a similar trip. And I was just walking by myself out of this forest, and they were like, what are you doing? I was like, what do you mean, what am I doing? They’re going back to town and they were like, you are alone, aren’t you afraid? And I was like, of you? Your who’s here with me. I think about that sometimes too that it didn’t even occur to me to be afraid. And I love thinking about that. I went to town, I stayed in this beautiful mountain inn for a couple of days and got over my cold. Then I took a bus back to the city and went back to the place where I was supposed to meet my boyfriend. When I think about it in retrospect, I think about how competent I was. Like, wow, you totally managed that. Like, that’s crazy. Like India is a very far away different place. And I was 18, 19 and knocking around there by myself alone, you know? And I was like, I’m just going to go do this thing. It didn’t even occur to me that I could not do it. That level of competence is pretty exciting.

Paulette:

Yeah. How do you think you’d be different if you had never gone on this big adventure?

Pam.

Oh my God. In a hundred thousand ways. We would not be having this conversation for starters, right? I got the fever so much about seeing the world and you know, what’s the opposite of xenophobia? I have that. I have this great love for far away places and the people that populate them. I don’t default to fear in the face of strangers. There’s a million ways I’d be different if I hadn’t done this. Like if I had just stayed home, I just can’t even imagine. When you get to the end of my book, I sort of tie it all up with this idea. I don’t feel like this is a spoiler, but that stuff makes us who we are, right? I wouldn’t be who I am today, if it was not for this formative adventure, you know?

Paulette:

Absolutely. Yeah. Formative is such a good word for it. Of course there were some gender-related issues that you come up against. You and I had talked about your sense of self and, you know, I think your sense of womanhood is what we can talk about first. You see so many different ways of being a woman revealed in different cultures. How did you come to see being a woman in the world? And how did that change your view from thereafter?

Pam:

Right. So it really depends on where you are, of course. Geography plays a huge role in this. I think increasingly less so, but not enough less-so in the world at large. I’m thinking maybe the U.S. is one of those places where it’s not enough less-so. I have a lot of opinions about that…burn down the patriarchy already! It is late! But I remember in Egypt and Pakistan, the way women lived at the time, they were very, very separate from men. And they dress differently and they behave differently and they could not be out in public by themselves. It was just not a thing that happened. So I sort of became aware of the fact that I was behaving in these ways that were not acceptable in these parts of the world.

But it’s funny though, when I think about it in retrospect, and I don’t really say much about it in the book, but I think as I’m thinking about it right now, I think about how, you know, I spent all that time in Israel and women and men both serve in the military, and they’re both trained in combat. And when you take a bus in Israel, you are just as likely to sit next to a beautiful young woman with perfect ringlets and an AK-47, as you are to sit next to a totally hot dude in perfect ringlets and an AK-47. And so in that culture, women do all the things in that society. And it depends where you sit in that society, because there’s these very conservative, Hasidic Jewish populations where women are relegated to these specific roles, but there’s also this other side of it where they’re literally on the front lines. Where you are really determines how women are perceived in the world.

Paulette:

And did that change how you perceived yourself? I’m so interested in how we humans are this tiny little point of consciousness. We can only see so much, and what we can see around us totally affects what we think is true, what we think of ourselves. Especially over time. I’ve found that if I do an extended trip I can really be surprised at how much it shifts my view. And then when I shift my geography, I’m like, Oh, wait, that’s not true at all. So for you, was there any kind of change in how you saw yourself as a woman or your own womanhood?

Pam:

I was so young that I’m not sure I even had that kind of specifically gendered identity. You know what I mean? I grew up on the 1970’s first wave of feminism, which seems super dated right now. Did I mention it’s late and we should be burning it all down? I think I might’ve mentioned that. So that’s what I was fed. Which meant that women were capable of doing things, and they maybe should have jobs and they maybe should have an education, but how they acted on those things might still be up for grabs. And you could get those things and then go back and have this very traditional heteronormative lifestyle regardless. So I don’t feel like it was very complete. So gosh, I don’t know. I don’t really know how to answer that.

Paulette:

Yeah. That’s okay. I feel like throughout the book, there’s kind of this concept of alarm bells that should have been going off, and people who should have been ringing those alarm bells but that didn’t happen for you. How did your view of taking care of yourself grow you as a person and maybe make you realize that you should have been taken care of a little bit better?

Pam:

I’m stupid independent. To a fault. And you’ve read the book. That is why. Geraldine DeRuiter wrote this blurb on the back of the book, and I’m just gonna read it. It’s not just to feed my vanity, but because it directly speaks to this point: “If you were skeptical of fairytales as a kid, the moral of this gritty story will resonate that sometimes the only person coming to save you is yourself.” You know, that is who I am now. I am insanely independent and it’s not necessarily the best thing. It’s like when I told you that my friend Alex asked me to write that story and I was like no, I’m depressed. It took me a long time to get help for that. Asking for help was a hard thing to do. Then when people who should be giving you help when you need it…you never see that. And you’re like, well, nobody’s going to help me. So I’m just going to deal. Right? So it’s not necessarily a great quality. It means I’m hyper competent, you know? I’ve been self employed for almost 20 years now and hyper competent at getting shit done, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that I’m fed well.

Paulette:

Yeah. I wanted to talk about your career actually, because it reminded me, in the book, when you went back to California and you’re in the mall and it’s just like, Oh, but you were just on the beach in Israel having this amazing thing. And it reminded me when I came back from Peace Corps, I was so broke that I had to get a temp job immediately. Two days after I came back from the Peace Corps, I’m in a cubicle the size of a phone booth. Just crying and inputting data. So that made me a freelance writer as well. ‘Cause once you’ve been in the wild there is no going back. So how did that lead into you becoming a freelancer and needing that freedom?

Pam:

What you’re saying makes sense to me. I don’t know that I would say it was that directed. Like I kept trying to get a job and then I kept quitting because I couldn’t reconcile the two-week vacation thing. I was like, no that’s crazy. Two weeks vacation is not enough for a living, breathing human. I need to go do things. And so it was a huge limitation. And freelancing makes it possible for you to be your own boss and to make that stuff happen for yourself. If you’re your own boss, you get to set your schedule. And I have busy times when I’m working all the time and I wish I could take a month off, but I’m like, you know what, you’re going to get that later, so calm down.

But when you’re a full time employee in a very traditional work-place, maybe you’re getting another week every year. Maybe you’re getting another two days every year. It was never going to be enough for me. It was never going to be enough for me. I was going to be like, I need six weeks. I need eight. The last time I had a full time job, which was early in the nineties, my negotiations stalled for a really long time, because I was like, this vacation package is ridiculous. I don’t care that I’m new. I can’t, I can’t. No, absolutely not. I ended up negotiating for a leave of absence as part of my contract. And actually, even then I only ended up being employed for nine months.

Paulette:

All right. That’s what I thought. Love that. Well, we’ll go ahead and take some questions from the audience. This one’s from Rich: How did your travels abroad make you feel about the U S? Envious? Defensive? Other? I found myself somewhat more “patriotic” during my years in Israel.

Pam:

Hi Rich. Thank you. When I first started traveling, and for the time period that this book takes place, I didn’t really know what it meant to be an American period. Like, I didn’t understand the context of that. I’m just out of high school and all I’ve got is a crappy public school history education. And it’s not until later that I acquire some sense of identity as an American. I became acutely aware of what I think of as American possibilities. Like in Britain, if you don’t figure out what you want to do by the time you’re 14 or something, you’re hosed, you’re just screwed. And that seems too young for that. So I liked that, as Americans, we seem to have more possibilities for reinvention. So I appreciated that about the nature of being American. But I also became super critical of global American policy because I saw the impact

Paulette:

Sarah wrote: I know that you have re-evaluated both some of your travel experiences and relationships in hindsight. Was it the writing process that forced that, or just growing up along the way?

Pam:

Writing this book was like cleaning out the attic. You know, I’ve been carrying around a lot of stuff up in the attic for a long time. I think probably a lot of it was reevaluated as I was writing the book over the last two and a half years. Writing the book was a lot of work. And I mean, like a lot of work up in here (in my head). Not necessarily just at the keyboard, not just the typing and crying, but the process of thinking about what these things mean. And I didn’t stop traveling when this book ends. I’ve been a traveler since I was 16 and I’m still very much a traveler. Definitely growing up has caused me to reevaluate the way I traveled some of those experiences. And I’m like, that’s messed up. Don’t do that. In a way that I wouldn’t have been when I was much, much younger.

Paulette:

Andrew asked: how would you compare your Jewish identity in Southern California versus your Jewish identity after living in Israel?

Pam:

My Jewish identity when I lived in Southern California was just like, I was just a Jewish kid in a Jewish family, and it didn’t really play a very big role in things for me. I didn’t live in a Jewish community. I don’t think that I knew that there was a Jewish community outside of these occasional Hebrew school interactions I had. It wasn’t a big part of my life at all. Living in Israel just made me aware of the fact that the Jewish community was a thing that existed. I don’t think I even knew that before. I don’t think I had access to that.

Paulette:

Okay. And Dorothy is here with the AP English question: Everything we do is motivated by deep needs. What do you think is your need or needs you are trying to meet in traveling? Freedom? Any others?

Pam:

You should read the book! You should read the book! I know you will read the book, Dorothy.

I really needed an education. And I think that my traveling definitely provided that in a very unconventional way. And I got a more conventional education later. I should have been in college. I really mean that. I should have been in college. I should not have been doing this. But this trip fed my deep curiosity to know about the world. And after you read the book, you’ll understand why I’m sort of being edgy about the question or twitchy about it. Because there’s so many other things going on, and it’s easy to think that I was looking for a place to be home. But I didn’t find that until many, many, many years later. And I might actually say that the first time that I felt at home was when I moved to Seattle, shortly before I turned 30. So it took me a very long time to find a place that felt like home. But probably that played part of it, that I was looking for a place to be home. Oddly, I was just going further and further and further away from places that could serve that role through the course of this trip. Instead of going back to where those things were actually available to me.

Paulette:

It’s almost like if home feels alienating, then I’m going to go somewhere else where I should feel that way. It’s too painful to feel that way in your own home. Like, if I’m going to feel like a stranger somewhere, I might as well feel like a stranger somewhere where I am a stranger. Yeah.

Pam:

That’s really well said. Yeah.

Paulette:

Yeah. So many feelings. Ok. I’m going to go off to type and cry myself!

So, Vaughn asked, after a lifetime of global travel, what is, or are your favorite locales or least favorite and the proverbial, why?

Pam:

So I used to try not to say that I didn’t like anywhere, that everywhere had something redeeming, and then I went to Missouri and I had to change that. Sorry, Missouri. So I think Missouri is my least favorite place that I’ve ever been. And probably because…Oh man, it was just the worst of America. I just found it so painful. My favorite is typically wherever I’m going to go next or where I just got back from. There were no bad places before I went to Missouri.

I went to Mississippi, I had the most amazing time. I went with my friend, Andy Murdoch to Elko, Nevada which is nowhere. We had an incredible time. Most places have something amazing to find, you know? In Elko, in this extremely charmless restaurant, we had the most amazing Palestinian meal. It was really spectacular. Really, really good food. If you look, you can find something good almost anywhere…except maybe Missouri. Sorry.

Paulette:

Alright.

Kevin asked: I’ve always found your writing to be deeply insightful, but this is another level. It’s raw. Do you feel exposed? Or glad you got through it? I, for one, am really moved to learn this part of your history.

Pam:

I feel terribly exposed actually. And nervous. It was hard. And I have intermittent anxiety attacks about how people are gonna react to the book. Specifically, my family members. Imagine carrying this around for so long and not putting it down. And so that part is awesome… to be like, this is outside of me now. I don’t have to think about it anymore. I can use all this space in my cleaned out attic for other things. I have bigger things to think about now than this thing that is 40 years old. And it’s big and it’s heavy and I’ve been dragging it around with me for a long time and it’s time to throw it out in the world and let it live on its own.

Paulette:

Love that. Yeah.

Winfield asks: where would you next like to explore, both location and experientially?

Pam:

So I’ve been working on this project called the Statesider, which is basically about travel in the U.S. American travel and culture. And as much as I did not enjoy Missouri, although Springfield is a nice town and I had a really good burger there. Also, there’s a place there where they make this thing that’s like a pie milkshake…where like it’s a milkshake… ice cream, milk, but they put pie in with it. I mean, come on! Right? I want that right now! So I’m really interested in the U.S. right. If I had all the money and time in the world to do something, I would go knock around the U.S. There are places in the U.S. where I’ve never been to. Oklahoma. You know, I’ve never been to Nebraska. I would like to see the Sandhill Cranes. I’ve never been to the Gulf Coast. The United States is diverse and interesting and fascinating, and we have a really deep history and we’ve done a really bad job of teaching ourselves about it. And I feel like it’s the responsible thing for us to do to understand our own country. And I haven’t done that to the degree that I would like to,

Paulette

Well, I grew up on the Gulf Coast, so that’s my home air. So I give you recommendations for sure. Right. On Facebook Douglas asked: It’s been a long journey going from writing the manuscript to pitching it to publishers…

I totally commend you. And I love how open you were about that process on Twitter. And then when it sold, like, I was like in on the win. I was there with you. And I loved that you did that.

Pam:

Thank you for cheering me on the whole way through! It was really helpful.

Paulette:

Cause it’s….yeah…this is kind of like…how I really define community and how do I know I’m in the community? When I started really feeling genuinely happy for the people around me and feeling like we’re all in this together. I was like, oh, this is what it is. Right. And that’s awesome.

So…Douglas asked: I’m wondering, what has Pam learned about herself in the process?

Pam:

I didn’t know that I could do this actually. You know, my friend Andrew who is here, was like, you’re fine. You’re going to get it done. Don’t worry about it. And I’ve had a lot of doubt. And it is amazing to me that this exists, right? Like when I went to Elliot Bay to do a signing, and they had this pile of books and I was like, Oh my God, they live in the world. I made a thing. And I didn’t necessarily believe that it would get picked up by a traditional market. I thought it would have to do it on my own. I didn’t think it was commercially viable. And remember I had been rejected 75 times. That was a lot of rejection. And I didn’t know. I probably should have, because I wrote a whole book about being tenacious. I probably should have known that I had the tenacity to do it, but I’m not sure that I believed it when I started it. I just was kind of on autopilot writing this thing because it felt like a thing that I had do. And then when it was done, I was like, that doesn’t suck. I should probably try to sell it. I had terrible imposter syndrome the whole time. I was like, Oh, I’m a fraud. The book’s no good. Nobody’s going to want to…you know…the typical writer garbage. And so I guess I was surprised that I had the endurance to work on a project that was this big for so long.

Paulette Perchach:

Hmm. Yeah. That’s awesome. Pete asked: what advice would you tell your pre-crazy-trip self in advance of the trip? Go or don’t go? And if go, duh, what would you tell her in advance?

Pam:

Of course I would go, duh…Break up with that guy. That’s bullshit. You deserve better. So absolutely that. And then, in advance, I would be like, read a book, Goddammit. Read a book. You know, guidebooks existed. They were not super prevalent for some of the places that I was in. I traveled with Lonely Planet’s very first commercially produced India guide, but it existed. And going to a place where you know nothing about the culture is a total idiot move. Don’t do that. Learn something, right? Like, you’re going to have to cover your head ‘cause that’s what people do there. If you’re a woman traveling in the Arab world, you need to cover your head. Read a book! Oh my God.

Paulette:

Right. Don’t make the person in the lobby of the hotel have to stop you on the way.

Pam:

Right. Don’t be that traveler! Right? Like learn your basic things. It’s not just please and thank you. It’s like, what are the baseline things that make this culture go? What are the baseline expectations for behavior that you should meet and…screw your sensitivity about how you get to be in these places and the way that you get to be in the rest of the world, because you don’t make the rules. Yes, women should get to travel with their heads uncovered. Yes, they should get all these things and they do not have them. And there’s no reason to make yourself a target because you’re carrying around a chip about that. And to be clear, I was not carrying a chip on my shoulder about it. I just did not know. And that is stupid. Don’t do that.

Paulette:

What would be your advice to people that age now who maybe want to take a gap year before college or something like that?

Pam:

There’s this really old piece of standard travel advice, but it’s a really good one, which is twice the money, half the stuff, right?

Paulette:

Yeah. That’s hard.

Pam:

Yeah. It is hard but worth it, right? Like you don’t need that extra sweater. What you need is another fifty bucks, right. That fifty bucks is going to get you something way better than that fancy zip fleece. Don’t. Save it. No one cares what you look like.

Paulette:

When I was reading this book, I was like, I don’t know how it’s going to make me feel to read a travel memoir right now. And I was so happy that it made me feel in love with travel again. Going along with the experience and kind of experiencing some of what I get from travel…of being like, Oh, I didn’t know that was there. This was like this, you know? Some of that awe, some of that wonder of the world that you get to experience. How have you, as a traveler, been getting through COVID and quarantine? And trying to live in that personality type that needs novelty and experience without being able to get that outside of your house?

Pam:

Badly, I’m getting through it badly. I mentioned there’s a chocolate cake in my kitchen and I’d been eating it. You know, I really love to get out of the house. Of course I do. I love to travel. I miss being able to go out in the world. I miss all those things, but I actually I’m very comfortable being alone in my house as an introverted kind of person. I’m like, I’m happy by myself. I didn’t think I’d spend this much time alone. This was not what I signed up for, certainly. But you know, not everybody on here is from Seattle, but I live in West Seattle right now. My neighborhood is basically a functional Island. It’s so idiotic. So getting anywhere is a huge hassle. So I’m kinda stuck with things the way they are.

I was talking earlier about that sense of being when you’re waiting for a ride, all you can do is look at where you are. So, you know, that’s what I’ve been doing. The other thing is that I’ve been working on this project. It’s called The Same River Twice. And it actually hasn’t been out of my hands for that long. So this has been really consuming. So my answer to that question might be different after winter is over. I’m really scared about winter here. You know, the weather is bad, it’s cold, it’s wet, it sucks. And getting outside is going to be increasingly more of a challenge. I worry about that a lot, but this…I think it’s maybe just two months that it’s been out of my hands. The amount of time from when I handed it off to when it went to press and was published and on the shelf was not very long. So my reality has been inside this book until very recently. And we’re going to find out how I’m doing, because I’ve just been in here instead of anywhere else.

Paulette:

All right. Well, I’m so excited for the book to be out and I loved it. So I’m going to be buying it for some Christmas presents.