Over the last decade, I’ve learned to control the texture of onions, the moisture in chicken, and the spiciness of curries, and yet, one element remains beyond my control: humans.

A few of them I’ve been dealing with since I was born, so I especially know what they need. But they won’t listen. They came without the control knobs of my stove, without the instruction manual of my Instant Pot, not giving any respect to my neurosis in the way of my beloved mandoline slicer.

A few years ago, I tried a new recipe with them: Start cooking and sipping wine early in the day, on a holiday culturally defined by cooking, with a family that has never wanted to cook. Sprinkle in some guilt and a dash of passive-aggressive hints, then, as it’s almost done, whip in the stress, turn on a broiler somewhere deep inside, and ruin Thanksgiving.

Last year, we ate out. And it was fine. Fine, the way any girlfriend is fine, with her shoulder pressed against the car door and her eyes shooting out the window. Which is to say, not fine. I mourned a Thanksgiving that existed only in my mind, but that I felt like I’d seen somewhere: women cooking together, bonding, working side by side.

This is the year I’m ready to drop it. To really be fine. Here’s why.

First, I hit up Michael Moss’ Salt Sugar Fat, which drew a straight line from a boardroom in New York to me on the couch, watching Saved by the Bell and drizzling icing on my breakfast of strawberry cream cheese Toaster Strudel. I ate junk food as a kid in the ‘80s because I was a kid in the ‘80s, and the ‘80s is when the junk food masters armed their battleships. When I was 6, Philip Morris bought Kraft, and used everything they knew about hooking smokers to hooking kids on sugar, salt, and fat.

That I have become the kind of person who owns a quinoa strainer is one of the great surprises of my life. Cooking is how I’ve started to love myself, how I love others. To me, all the prep and planning is worth it for that moment when the people you’ve gathered together at a dinner party start to meld, the way someone who was a stranger to everyone in the room an hour ago bounces a joke off one of your oldest friends. I wanted that for us.

I wanted to be loved in that way. I’d wanted my mom to love me in that way ever since the days of eating the cafeteria food in elementary school and watching the kids with the lunches from their mom.

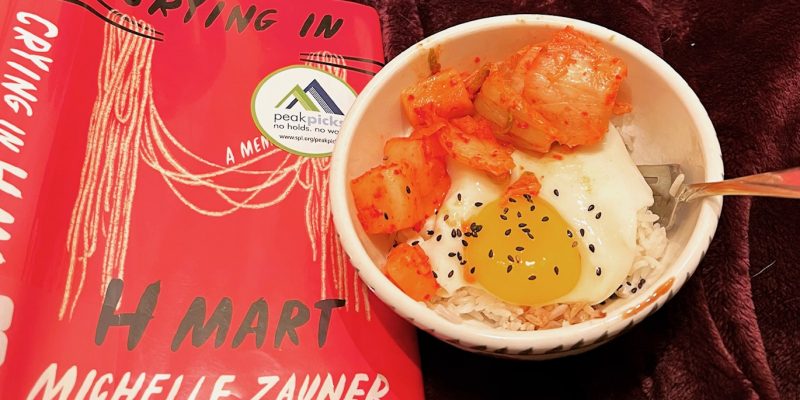

Michelle Zauner’s mom loved her in that way. It was my fondness for Korean food and the fact that I saw her book, Crying in H Mart, everywhere that made me pick it up. From the get-go, the book is filled with kimchi-flavored food porn. I finally said, “Ok, that’s it!” while reading it, and had to get up and fry an egg with some kimchi to continue. For Michelle, food is an edible form of love from her mother.

The love of Michelle’s mom is nearly an inverse of the love of mine. My mother, whose own mother cooked but never taught her to cook, fed me with the promise of fast food and industrialized food to make our lives easier: KFC, powdered cheese packets, Dunkin Donuts, but also homemade pancakes, carrot sticks, and cut-up fruit. Michelle’s mom perfected a variety of Korean foods, and always remembered how each person liked theirs.

However, Michelle’s mother also had a hard shell around her love and a magnified eye on every detail of how Michelle presented herself. She called things she did slutty, picked at the way she dressed and talked. Worse, after going to Michelle’s first show as a guitarist, she told her she was just waiting for her to give it up, that she regretted ever getting her lessons.

Meanwhile, the dedication on my book reads, “For my mom, who always said, ‘Just follow your heart, honey.’” My mom has never made me feel not good enough. She has always loved me unconditionally and been there when I needed someone, which has been often. She raised three of us while working and managing a bankruptcy, with hardly time to read non-fiction books about the industrialized food industry.

From page one, you know Michelle’s mom is going to pass away from cancer, and you spend the rest of the book watching it happen. Having already lost one parent, it was a reminder to me how precious the rest of my time is with my mom.

Why are we so hard on our moms?

So when she called this year to ask, “Is Boston Market ok this year?” I said yes, and it truly, truly was. As Michelle says in the book, at some point, the small criticisms just aren’t worth it anymore.

And that, my friends, is how books change your life.